20 Dec

2022

Court reporter shortage: A misnomer with a people-centered solution?

The U.S. “court reporter shortage,” which Californian court officials this month labelled “a crisis,” can be resolved without descending into a jobs-versus-technology argument.

Best-practice digital court recording systems already provide an efficient and reliable solution, combining secure and fit-for-purpose technology that supports—rather than replaces—people who capture, and are responsible for, the record.

The issue of the stenographer shortage was highlighted on November 2, 2022 by 54 Californian trial court CEOs, who released a joint media statement calling for a review of their state’s statutory framework for court reporting. The CEOs said the framework “inhibits creative responses” to the stenographer shortage.

Without specifically calling for video and audio recording to be permitted in all courtrooms state-wide, the CEOs cited Government Code §69957, which prohibits electronic recording in civil, family law, and probate courtrooms, except in limited cases.

“With current statutory framework for court reporting, all courts will face the inevitable day, already seen by a few California courts, of not having enough [stenographic] court reporters to cover the mandated felony criminal and juvenile dependency and delinquency cases,” the statement read.

“Every litigant in California should have access to the record. Ideally, this would be provided by a [stenographic] court reporter but when none are available, other options need to be available to the courts.”

The statement’s hinted-at solution does deserve serious consideration—because electronic court recording has been successfully supporting access to justice in thousands of jurisdictions around the world for the past three decades.

Such systems take the pressure off existing workforces of stenographic court reporters, by being set up and ready to go at any time.

But installing digital equipment need not mean an additional workload for court clerks, associates, or other administrative staff. Many courts engage electronic or digital court reporters—certified court reporters who are trained to operate court recording technology to capture the verbatim record, and who often also provide certified written transcriptions or engage official transcribers to deliver certified transcripts.

“There is not a court reporter shortage in the United States, there is a stenographic court reporter shortage,” says Margaret Morgan, a District Court Reporter in Minnesota, who has been an electronic court reporter for over 28 years.

“Stenographic reporters have done great work for years, but there are alternatives, equally capable, to capture an accurate and complete record.”

The Minnesota Judicial Branch experience

Mrs. Morgan and her Minnesota Judicial Branch IT and electronic or digital court reporter colleagues work closely with For The Record as their justice technology provider to ensure the recording systems they use are fit for purpose, respond to changing demands and technology innovations, and are easy to operate. Furthermore, while the technology systems themselves are reliable, the people trained to run and monitor them—digital court reporters—provide the human touch which amplifies the success of these digital methods.

With more than 30 years’ experience developing and installing court recording solutions across more than 70 countries, For The Record’s flagship court recording software, FTR Gold, is used in more courts internationally than any other justice recording system.

FTR Gold and Cloud Platform Solutions set industry benchmarks, bringing together the highest quality audio and video recording with secure online storage, management, and access.

Some jurisdictions, however, have not yet embraced such technology, as they work to manage reduced budgets, resource allocation, restrictive statutes, and the perceived risks of new technology. As such, the Californian CEOs’ statement provides the opportunity to address some of these perceived risks and the “myths” surrounding digital court records.

Busting the digital court recording myths

For The Record CEO Tony Douglass (TD) is considered a pioneer in the world of digital court recording, having created one of the world’s first public e-courts almost 30 years ago.

Mr. Douglass addresses some of the long-standing myths of court recording…

Myth: Court recording equipment is left unmonitored and can fail mid-hearing.

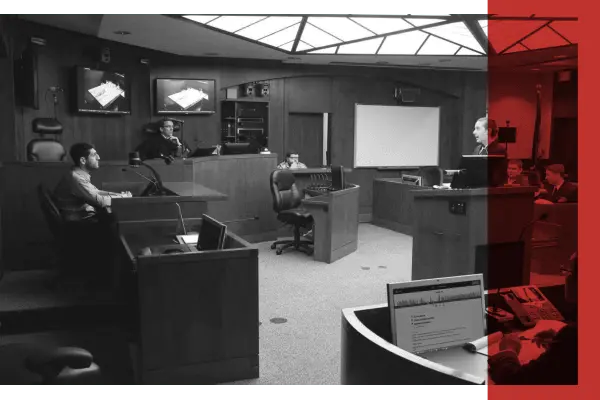

TD: Digital court reporters or court monitors are involved in the process to ensure the technology is working before, during, and after proceedings. They perform what is called ‘confidence monitoring’ and create annotations of the proceedings that are linked to the recording to help with later transcriptions or searches. Each morning, both the digital court reporter and our systems run a series of tests of the courtroom technology to ensure all audio and visual recording systems are working as expected and required before the judge arrives.

Myth: In a courtroom, a stenographer will ask for testimony or questions to be repeated, especially when people are talking over the top of each other. Digital recording equipment can’t do that.

TD: FTR Gold provides multichannel recording with up to 32 channels of high-fidelity audio and four channels of HD video. That means a transcriber can isolate each channel to clearly hear what was said and by whom, while the video provides additional context, especially when parties are arguing and cross-talking. With this capability, there can be fewer interruptions to proceedings in the courtroom—though digital court reporters are still present to correct situations that impact the court record if required.

Myth: The ambient sound in the courtroom compromises the clarity of the audio recording, making it difficult to transcribe accurately.

TD: Algorithms and our own FTR Smart Audio technology ensures background noise such as air conditioners, rustling papers, or other sounds in the courtroom are reduced or eliminated. Our combined microphone/speaker bases have been designed to ensure courtroom participants can hear each other and remote parties clearly, without compromising the quality of the courtroom recording. Our recording equipment truly captures audio in the courtroom of each participant better than the human ear and is capable of capturing exactly what is spoken during proceedings.

Myth: The digital court record is easily lost—recorded over, not recorded at all, or interfered with.

TD: We have strict redundancy measures in place to ensure recordings are secured as they are created. Multiple backup recordings are captured simultaneously and stored on secure servers and in the cloud, where they are safeguarded with multiple layers of defenses, including digital checksums, activity logging, and encryptions to protect against theft, hacking, file corruption, and unauthorized deletion.

There’s room for all court reporters

In California, the The Rules of the Californian Court for electronic recording were last updated in 2007. In a digital, cloud-based world, those rules still refer to “reels” of tape—an analogue term mostly considered obsolete.

Mr. Douglass says the future of courts—whether in California or in Kenya—is digital, but there will always be a need for human involvement.

“Our solutions are designed with courts in mind and are people-centered,” he says. “They not only increase access to justice for participants in proceedings who are external to courts (i.e., parties, the public etc.), but they also ensure court staff can continue to support the justice system to deliver on promises of transparency, efficiency, and accessibility.

“They help jurisdictions meet compliance and uphold the sanctity of the judicial system. High quality digital court recordings will always provide a clear, accurate and available record for review of proceedings exactly as they happened, for future transcription, for further review or appeals—or even as a high-quality backup for stenographic court reporters to refer back to.”

Margaret Morgan says her experience in the Minnesota Judicial Branch over almost 30 years shows how technology aids access to justice—and doesn’t replace people in the process.